Exoplanets searches are underway all over the world. Space agencies, universities, non-profit organizations, and large telescope facilities are all engaged in, not only finding exoplanets, but also finding exoplanets that could harbor life as we know it. The goal is to find exoplanets that have the right conditions to support life.

Exoplanets searches are underway all over the world. Space agencies, universities, non-profit organizations, and large telescope facilities are all engaged in, not only finding exoplanets, but also finding exoplanets that could harbor life as we know it. The goal is to find exoplanets that have the right conditions to support life.

Exoplanet research is acquiring new data daily so fast that it is difficult to process the data into knowledge. Several groups are maintaining a list of exoplanets discoveries resulting in slightly different counts of official exoplanets.

The Kepler Mission is a NASA Discovery Program for detecting potentially life-supporting planets around other stars. All of the extrasolar planets detected so far by other projects are giant planets, mostly the size of Jupiter and bigger. Kepler is poised to find planets 30 to 600 times less massive than Jupiter.

There is now clear evidence for substantial numbers of three types of exoplanets; gas giants, hot-super-Earths in short period orbits, and ice giants. The challenge now is to find terrestrial planets (i.e., those one half to twice the size of the Earth), especially those in the habitable zone of their stars where liquid water and possibly life might exist.

How?

Most planets are currently discovered by the planet transit method. When we see a planet pass in front of its parent star it blocks a small fraction of the light from that star. When that happens, we say that the planet is transiting the star. For comparison, a central transit of the Earth crossing our Sun lasts 13 hours if viewed by life on an exoplanet.

If we see repeated transits at regular times, we have discovered a planet! From the brightness change, we can tell the planet size. From the time between transits, we can tell the size of the planet’s orbit and estimate the planet’s temperature.These qualities determine possibilities for life on the planet.

To detect an Earth-size planet, the photometer must be able to sense a drop in brightness of only 1/100 of a percent. This is akin to sensing the drop in brightness of a car’s headlight when a fruitfly moves in front of it!

The following websites are tracking the day-by-day increase in new discoveries and are providing information on the characteristics of the planets as well as those of the stars they orbit: The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopedia and NASA Exoplanet Archive.

Current NASA Exoplanet Archive Holdings (May 23, 2012)

2,321 Kepler Planetary Candidates

1,407,323 Transit Survey Light Curves

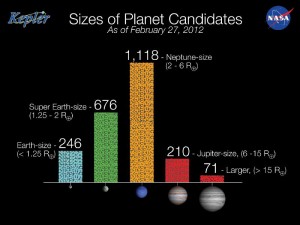

Kepler Planet Candidates (2,321) by Size, Feb. 27, 2012

This histogram summarizes the Kepler Planet Candidate catalog, which contains 2,321 planet candidates identified during the first 16 months of observation conducted May 2009 to September 2010. Of the 46 planet candidates found in the habitable zone, the region in the planetary system where liquid water could exist, only ten of these candidates are near-Earth-size.

This histogram summarizes the Kepler Planet Candidate catalog, which contains 2,321 planet candidates identified during the first 16 months of observation conducted May 2009 to September 2010. Of the 46 planet candidates found in the habitable zone, the region in the planetary system where liquid water could exist, only ten of these candidates are near-Earth-size.

Credit: NASA Ames/Wendy Stenzel

Considering that we want to find planets in the habitable zone of stars like the Sun, the time between transits is about one year. To reliably detect a sequence, one needs four transits. Hence, the mission duration needs to be at least three and one half years. It stares at the same star field for the entire mission and continuously and simultaneously monitors the brightnesses of more than 100,000 stars for at least 3.5 years. If the Kepler Mission is extended beyond the planned 3.5 years, it will be able to detect smaller, and more distant planets as well as a larger number of true Earth-like exoplanets.

Click here to view NASA PlanetQuest to learn more about exoplanet searches